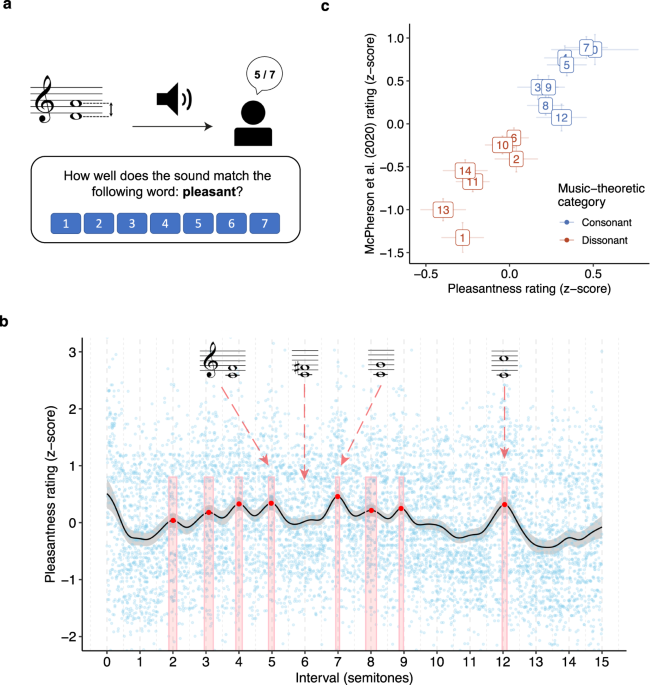

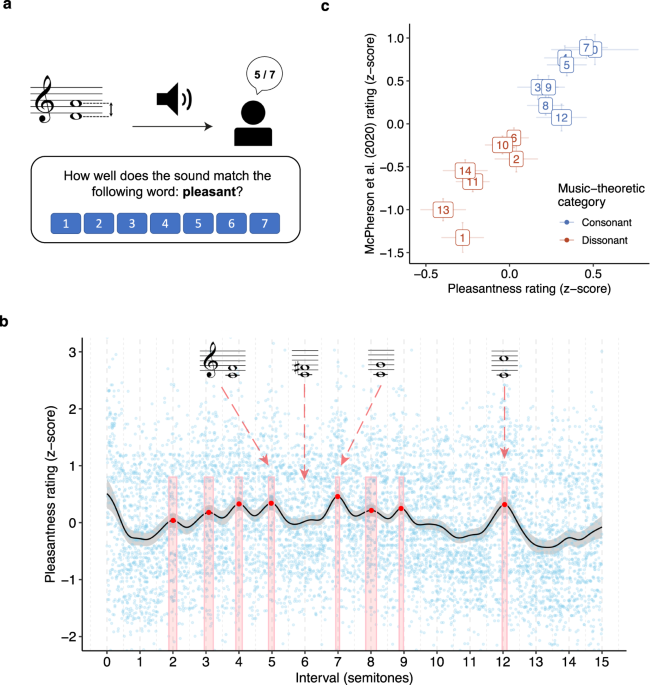

Interesting to see this piece of research.

I did research on a similar thing in 1979. I was wondering why the gender wayang (photo of instruments attached) that I brought home from Bali and sounded so great there, turned out to sound so bad and out of tune after a few weeks back in California. I wondered... did the difference in humidity screw things up with the bamboo? Nah... these are metal bars, right?

Another question I had was around tuning. Gamelans are not tuned often. Genders, for instance, maybe every hundred years? That might have been a joke, because the Balinese sense of time is very different... but probably not more than every 20 years. Certainly not like we obsessively tune western instruments.

And in looking at primary intervals like octaves, those could range between a major 7th and a minor 9th in practice. So what about that?

Thus I was inspired to do a research project on it.

Incidentally, a gender is way brighter than a bonang, so I think there would be even more impact of the inharmonicity.

Anyway...

I sampled the 2 larger gender wayang and then did DSP analysis to break out the individual overtones (which of course were inharmonic). I could take that data and from it resynthesize (additively) new gender tones and they would be identical to the original recording. I could also add in another overtone that was not there. This I did at an octave above the fundamental frequency. Turned out there was a hole in the original set of partials at the octave. Also, the original gender tuning had highly stretched octaves.

Then I had my resynthesized instruments play a familiar gender wayang piece. The tune was created in four conditions:

1. Original gender scale tuning, original series of overtones.

2. Original gender scale tuning, overtones included my added one at the octave.

3. Modified gender scale tuning (octave set to an octave), original series of overtones.

4. Modified gender scale tuning (octave set to an octave), overtones included my added one at the octave.

I took this back to Bali and played it for professional gender players as well as for the 3 gong makers on the island who tuned instruments. And asked (with the proper scientific protocol) which they preferred when the various of the four conditions were paired off. It seems that when the octave-added overtone series was used, they preferred the in-tune octave scales. When the octave overtone was not there, as in the original series of overtones, they liked the original tuning.

So I realized that after I had returned to California and was again hearing a bunch of western tuning (I played piano, and yes, stretched octaves there too, but not nearly like in the gender)... it was not the instruments that changed. It was my brain.

www.cam.ac.uk

www.cam.ac.uk

www.nature.com

www.nature.com

??!!

??!!